Getting lean is often described as “losing fat while keeping muscle,” but in practice, many people experience the opposite. They lose weight quickly, yet their strength drops, muscles look flatter, and progress becomes harder to sustain.

This leads to a common question: is it actually possible to get lean without losing muscle?

The answer is yes — but not in the way most people attempt fat loss.

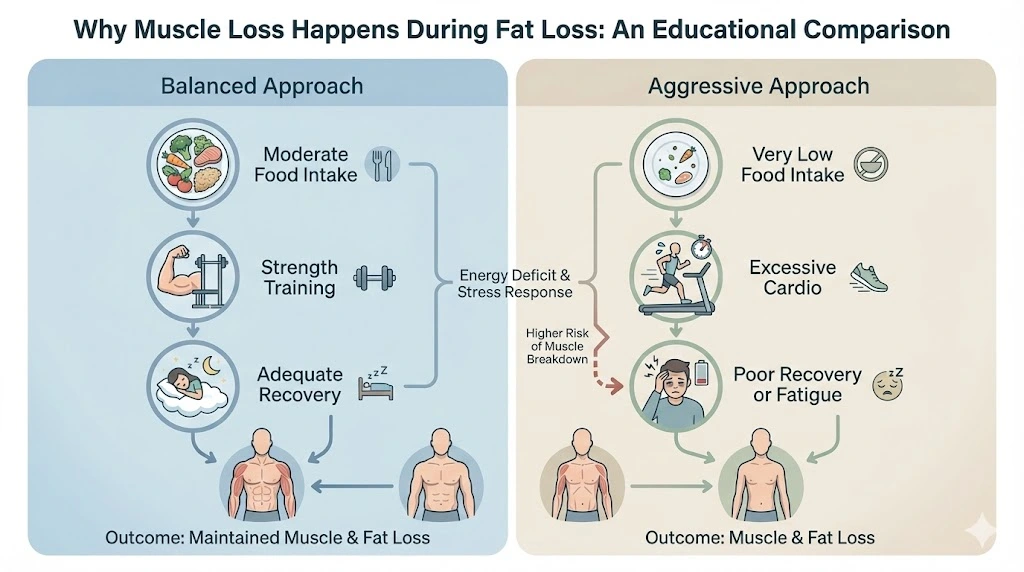

Muscle loss during cutting is rarely caused by dieting itself. In most cases, it happens because fat loss is approached too aggressively, without giving the body enough time, nutrients, and recovery to adapt. Understanding this difference is the key to getting lean while staying strong.

This guide explains how to get lean without losing muscle by focusing on training signals, calorie management, recovery, and realistic fat-loss timelines — rather than extreme dieting rules.

Is It Possible to Get Lean Without Losing Muscle?

Yes, it is possible to lose body fat without losing muscle, but it is conditional, not automatic.

Muscle is retained when the body receives a clear signal that it is still needed. That signal comes primarily from resistance training, supported by adequate nutrition and recovery. When this signal is weak or inconsistent, the body becomes more willing to break down muscle tissue during a calorie deficit.

Fat loss and muscle retention must work together. When fat loss is rushed, or when recovery is compromised, the body prioritizes survival over performance. This is why two people can follow similar calorie targets and experience very different outcomes.

Getting lean without losing muscle depends less on chasing perfect numbers and more on maintaining strength, managing fatigue, and allowing the body to adapt gradually.

Why People Lose Muscle When Cutting (Even With “Good” Diets)

One of the most common reasons people lose muscle during fat loss is creating a calorie deficit that is much larger than they realize.

Many people do not track calories accurately and assume they are eating “a little less,” when in reality the deficit is significant. When this is combined with high amounts of cardio, total energy availability drops rapidly. The body is then forced to compensate, often by breaking down muscle tissue.

Excessive cardio during a calorie deficit is another major contributor to muscle loss. When food intake is already reduced, adding large volumes of cardio increases energy demand even further. Without sufficient nutrients and recovery, muscle becomes a secondary priority.

Another major mistake is reducing calories too aggressively at the start. Dropping intake suddenly — for example from a high-calorie intake to very low levels — places the body under immediate stress before it has adapted. Training performance declines, recovery suffers, and muscle loss becomes more likely.

In practice, muscle loss during cutting is rarely the result of one factor alone. It is usually the combination of an overly aggressive calorie deficit, excessive cardio, and inadequate recovery that leads to strength loss and muscle breakdown.

Fat Loss Speed vs Muscle Retention (Where Most People Go Wrong)

One of the biggest factors determining whether you lose muscle while cutting is how quickly the calorie deficit is introduced.

Fat loss happens when energy intake stays below energy expenditure for long enough. Muscle retention, however, depends on whether the body can adapt to that deficit without compromising recovery and training performance.

When calories are reduced too aggressively, the body experiences a sudden drop in available energy before it has time to adjust. Strength levels fall, fatigue accumulates, and recovery between workouts becomes incomplete. In this state, preserving muscle becomes secondary to conserving energy.

This is why rapid drops in calorie intake — such as cutting food intake in half overnight — often backfire. Even if fat loss initially appears faster, the cost is usually reduced training quality and increased muscle breakdown.

A slower, more controlled approach allows the body to adapt to the deficit while maintaining strength. When training performance remains stable and recovery is adequate, the body has a reason to hold on to muscle tissue while using stored fat as fuel.

In practice, people who lose fat at a moderate pace tend to maintain more muscle, feel better during the process, and sustain results longer than those who attempt extreme cuts.

Fat loss speed is not just a preference — it directly affects how much muscle you keep.

The Training Signal That Tells Your Body to Keep Muscle

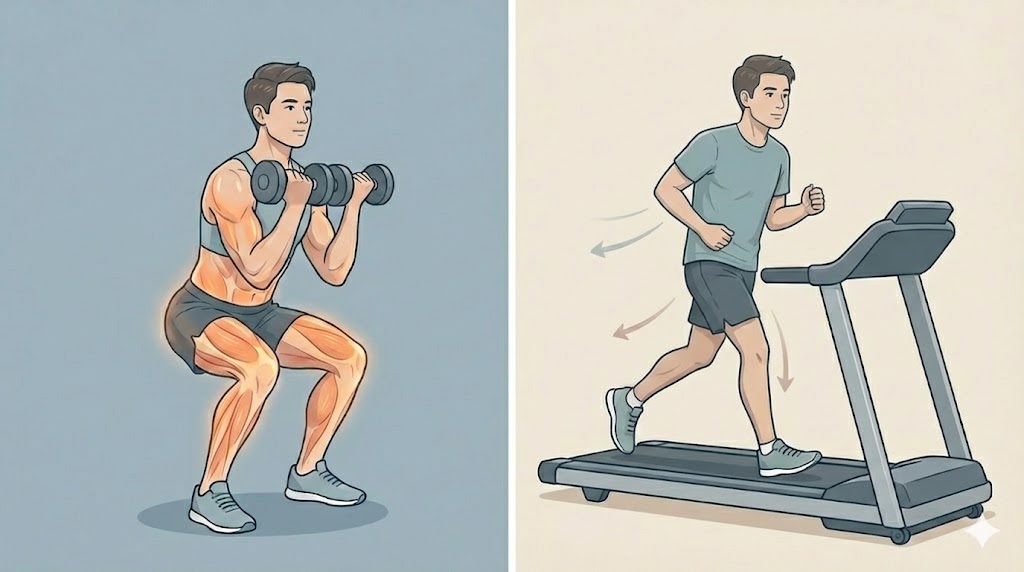

Muscle tissue is metabolically expensive. During a calorie deficit, the body continuously evaluates whether maintaining that tissue is worth the energy cost. The primary factor influencing this decision is mechanical tension produced through resistance training.

Strength training sends a clear signal that muscle tissue is still required for performance. When that signal is strong and consistent, the body is more likely to preserve muscle mass even while energy intake is reduced.

During fat loss, the goal of training is muscle retention, not constant progression. Trying to increase volume, frequency, or intensity aggressively while calories are low often increases fatigue faster than the body can recover. This weakens the very signal meant to protect muscle.

In practice, maintaining strength on key lifts is a more reliable indicator of muscle retention than chasing new personal records. When strength levels remain relatively stable, it suggests that muscle tissue is being preserved despite the calorie deficit.

Excessive cardio can interfere with this process. High volumes of endurance work increase overall energy expenditure and recovery demands without reinforcing the muscle-retention signal. When combined with an aggressive calorie deficit, this can shift the body toward breaking down muscle for energy.

Effective fat loss training prioritizes:

- Consistent resistance training

- Sufficient intensity to maintain strength

- Manageable volume that allows recovery

When training quality is preserved, the body receives a clear message: muscle tissue is still needed.

Protein, Calories, and Why “Enough” Beats “More”

When trying to get lean without losing muscle, nutrition supports the process — it does not override training and recovery. Protein and calorie intake matter, but muscle retention is not improved by chasing extremes.

Protein helps preserve muscle by supporting repair and reducing muscle breakdown during a calorie deficit. However, beyond a certain point, increasing protein intake further does not continue to protect muscle if training quality and recovery are poor.

For most people cutting fat, consuming adequate protein relative to body size and activity level is sufficient. Very high protein intakes may offer diminishing returns while increasing fatigue, digestion issues, or diet rigidity that makes consistency harder to maintain.

Calories play a similar role. Muscle loss is more strongly associated with how large and how sudden the calorie deficit is, rather than the exact number itself. A moderate deficit that allows training performance to remain stable is far more protective of muscle than an aggressive deficit paired with perfect macros.

In practice, muscle retention improves when:

- Protein intake is sufficient and consistent, not maximized

- Calories are reduced gradually, not abruptly

- Food intake supports recovery and training quality

Obsession with exact targets often creates stress without improving outcomes. When nutrition supports performance and recovery, muscle retention tends to follow.

Why Women Often Experience Muscle Loss Differently During Fat Loss

Women can absolutely get lean without losing muscle, but the process often feels different compared to men due to differences in energy availability, recovery tolerance, and hormonal regulation.

During fat loss, women generally operate closer to their minimum energy requirements. This means that aggressive calorie deficits are more likely to interfere with recovery, training performance, and muscle retention. When energy availability drops too low, the body prioritizes essential functions over muscle maintenance.

Another factor is how fatigue accumulates. Many women are able to maintain discipline during dieting but continue to train at high volumes or add excessive cardio. Over time, this combination creates a recovery gap — strength may decline even when protein intake appears adequate.

Muscle retention in women during fat loss tends to improve when:

- Calorie deficits are introduced gradually

- Strength training focuses on maintaining performance rather than increasing workload

- Cardio is used strategically, not excessively

- Recovery markers such as sleep quality and training energy are prioritized

It’s also important to recognize that scale weight changes may look different. Water retention, menstrual cycle fluctuations, and glycogen shifts can mask fat loss progress, leading some women to cut calories further than necessary. This often increases muscle loss risk without accelerating fat loss.

A patient, performance-focused approach allows women to maintain strength and muscle while leaning out, even if visual changes occur more slowly. In the long term, this approach leads to better body composition and more sustainable results.

Signs You’re Losing Muscle (And Should Slow Down)

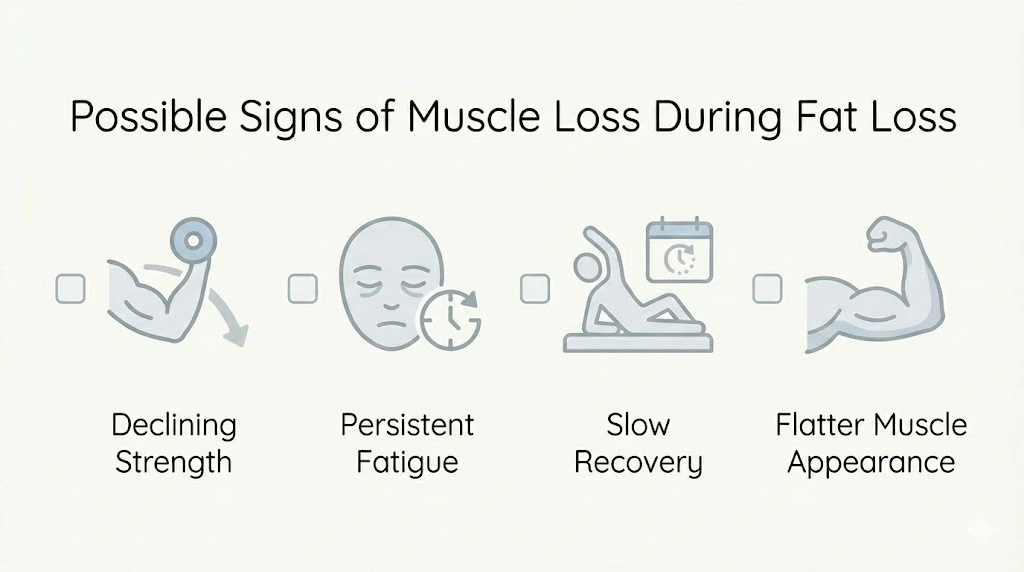

Muscle loss during fat loss does not usually happen overnight. It tends to show up through consistent patterns rather than sudden changes on the scale.

One of the earliest signs is a noticeable drop in strength across multiple training sessions. Occasional bad workouts are normal, but when strength declines steadily despite adequate effort, it often signals insufficient recovery or an overly aggressive calorie deficit.

Another indicator is persistent fatigue that does not improve with rest days. When energy levels remain low, training quality suffers, and the muscle-retention signal weakens. Over time, this increases the likelihood of muscle breakdown.

Changes in muscle fullness can also be a clue. While some flatness is normal during fat loss due to reduced glycogen and water, prolonged loss of muscle “density” combined with declining performance may suggest that muscle tissue is being lost rather than temporarily depleted.

Additional signs include:

- Longer recovery times between workouts

- Decreased training motivation tied to physical exhaustion

- Increased soreness that lingers longer than usual

These signals do not mean fat loss has failed. They indicate that the current approach may need adjustment. Slowing the rate of fat loss, reducing cardio volume, or increasing recovery often helps preserve muscle while allowing fat loss to continue.

Listening to these patterns early prevents small issues from turning into significant muscle loss.

What Not to Do When Trying to Get Lean

Trying to get lean often fails not because people don’t work hard enough, but because effort is directed in the wrong places.

One common mistake is cutting calories too aggressively too early. Large, sudden deficits may accelerate scale weight loss, but they also increase fatigue, reduce training quality, and raise the risk of muscle loss. Fat loss works better when the body is given time to adapt.

Another issue is relying on excessive cardio to create fat loss. While cardio can be useful, using it as the primary tool—especially on low calories—often interferes with recovery and weakens the muscle-retention signal provided by strength training.

Over-focusing on exact macro targets can also backfire. Chasing perfect protein numbers or constantly adjusting calories often creates unnecessary stress without improving results. Consistency in training performance and recovery matters more than hitting precise daily targets.

Finally, judging progress solely by scale weight leads many people to make unnecessary changes. Short-term fluctuations in water and glycogen are normal during fat loss and do not always reflect fat or muscle changes. Reacting too quickly often results in cutting calories further than needed.

Avoiding these pitfalls allows fat loss to remain sustainable while preserving muscle and strength.

The Bottom Line

Getting lean without losing muscle is not about extreme dieting, perfect macros, or endless cardio. It’s about maintaining the signals that tell your body muscle is still needed while allowing fat loss to happen at a pace the body can adapt to.

Muscle retention depends on consistent strength training, adequate recovery, and a calorie deficit that is introduced gradually rather than abruptly. When training performance is preserved and fatigue is managed, the body is far more likely to use stored fat for energy while holding on to muscle tissue.

Progress during fat loss should be judged by trends in strength, recovery, and overall performance—not just changes on the scale. A patient, structured approach may feel slower at first, but it produces leaner results that are easier to maintain.

Leanness is not achieved by doing more, but by doing the right things consistently over time.